Listening Ecologically

David de la Haye MMus, MIScT, AfCGI

01 August 2023

Introducing concepts of soundscape ecology, field recording and eco-art

Aims & Objectives

- The idea that richness of sound directly relates to richness of life is compelling and accessible. I aim to introduce the potential of using sound to better understand life below water (SDG14).

- The life aquatic is anything but silent. Human ears fail in these environments but augmenting our senses using underwater audio technologies alters our listening perspective.

- To accelerate knowledge exchange across the arts and sciences and re-establish the cultural value of water.

“All of the sound we hear is only a fraction of all the vibrating going on in our universe.”

David Dunn - Acoustic Ecologist

Acoustic Ecology

- Acoustic Ecology is an interdisciplinary field that investigates the relationship between sound and environment on multiple temporal and frequency scales.

- Lowering an underwater microphone (hydrophone) into a body of water and listening is all it takes to reveal an unheard orchestra of sounds produced by frogs, fish, insects, crustaceans, and even plants. It gives a new perspective of familiar spaces.

Listen to this recording made at a local pond.

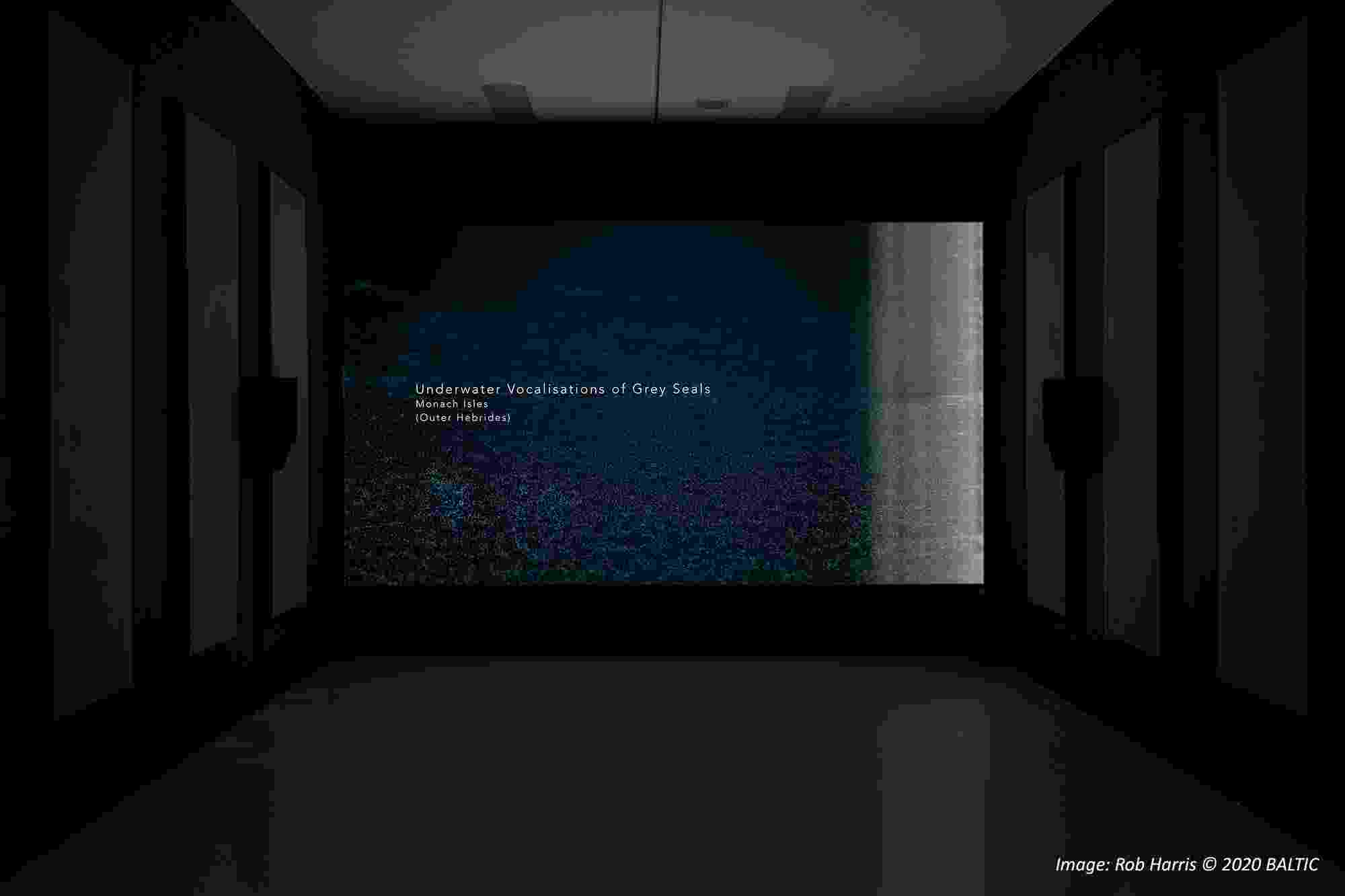

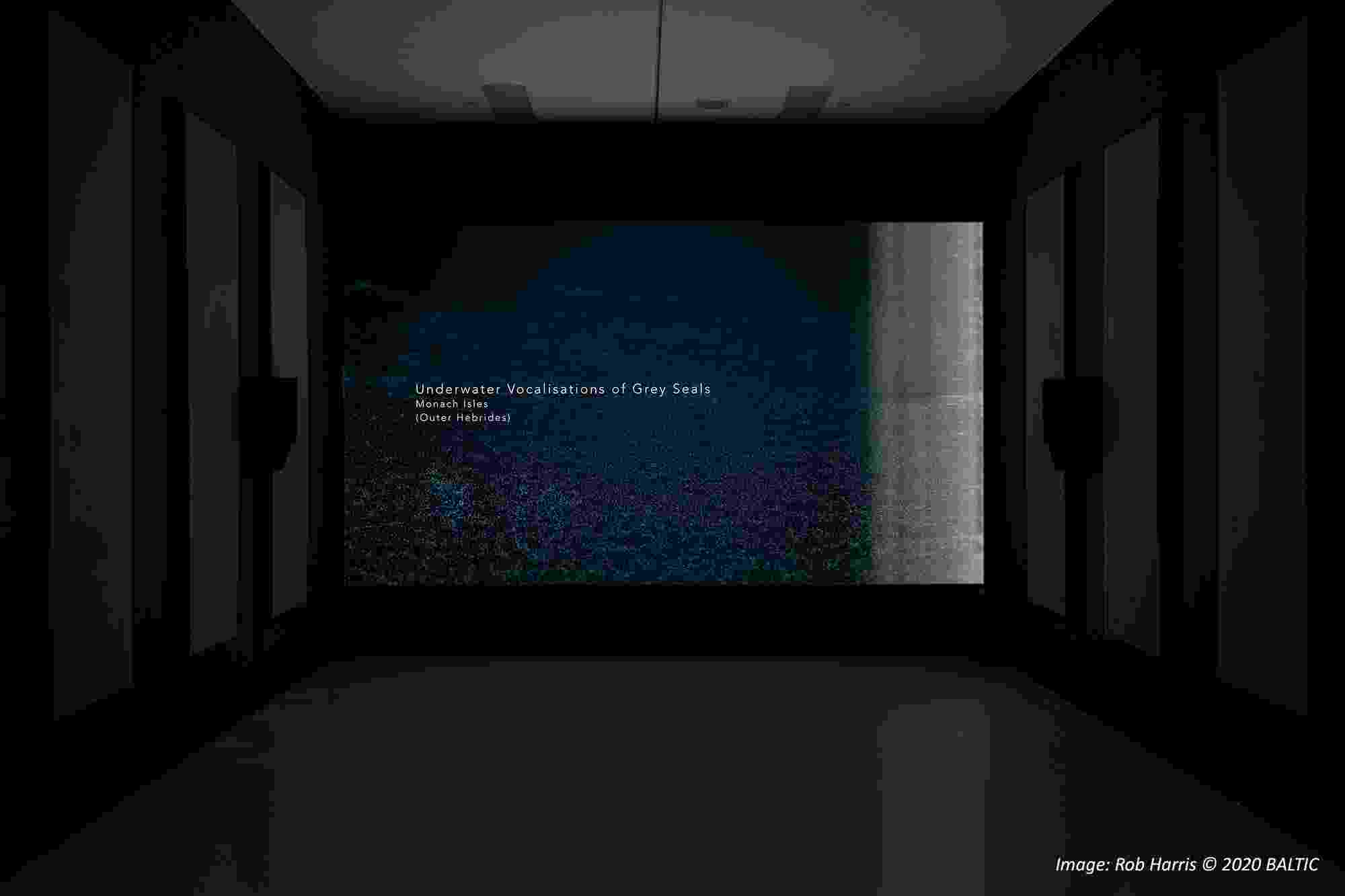

Image: “From Sea to Skye: An Ocean of Sound”, BALTIC Open Submission installation view. BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead. Photo: Rob Harris © 2020 BALTIC

Artistic Merits

- Sound can make difficult concepts relatable. Statistics might indicate biodiversity in real terms, but art provides a method to make difficult concepts a reality.

- By connecting creative discovery with scientific impact, eco-art seeks to generate “empathetic responses that have the capacity to inspire climate action” (Barclay, 2019).

- Sound is the first sense we develop. It penetrates the body and physically resonates with us.

- It fulfils the basic desire to be heard, and initiates an interspecies dialogue which gives a voice to the non-human.

“It is when the ear is surprised by sound, (…) when we become overwhelmed by sound, the source of which we cannot see, and for even a brief moment is mysterious to us, that awe, wonder or even terror strikes us.”

Seán Street - Writer, Poet and Broadcaster

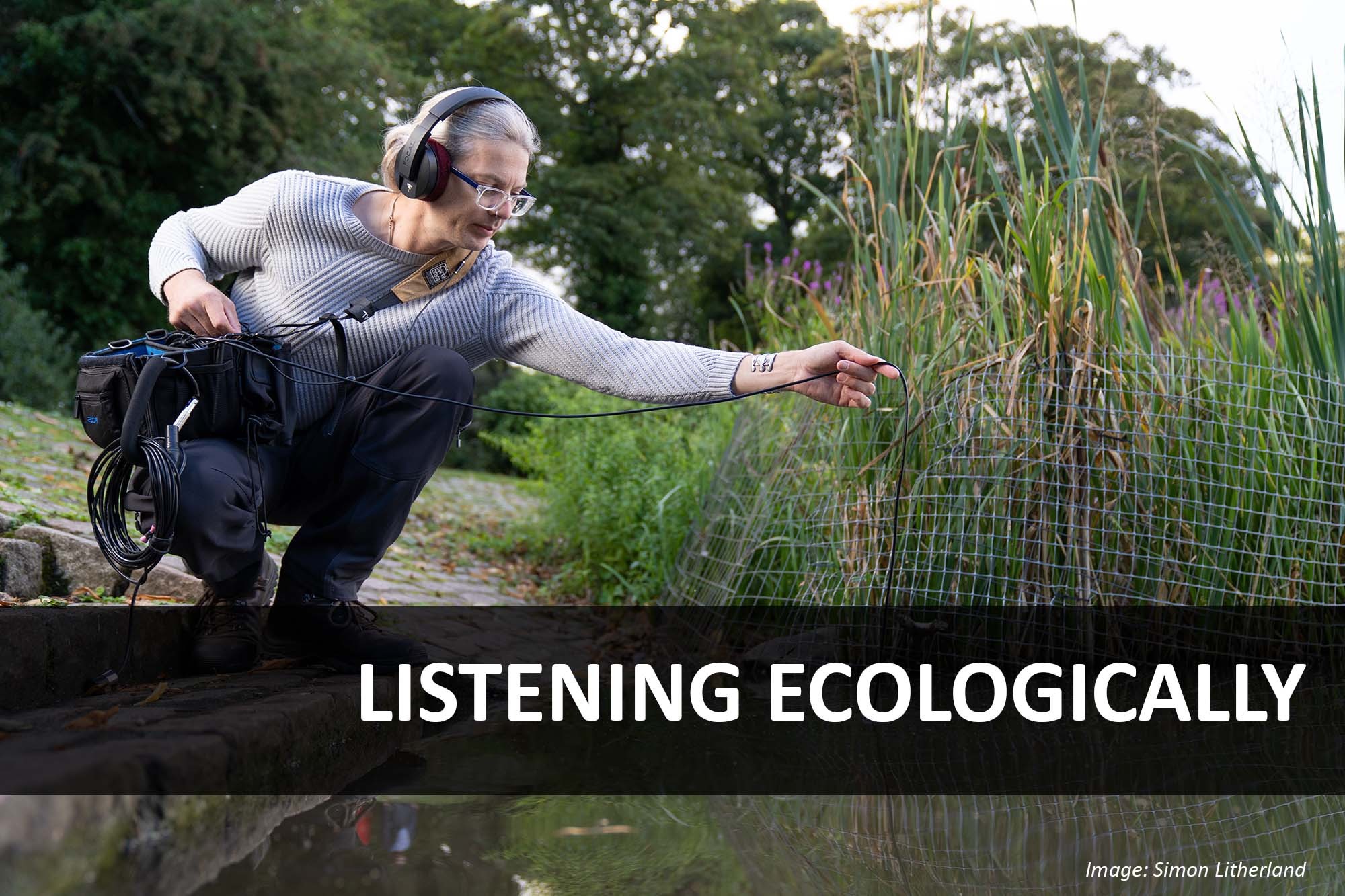

Image: Mhairi Hall

In The Field

- Microphones can be used as tools to heighten aural perception and encourage listening as an active process. Their sensitivity induces hyper-awareness of the acoustic imprint we, and others, leave on the landscape.

- The sonic exploration of ponds became a distraction and obsession during periods of lockdown. Easy to access, they provided complex soundscapes not dissimilar to an imagined rainforest; no need to travel the world searching for exotic locations - here they are, on our doorstep.

- Most digital recorders have the ability to add metadata. This might include date, time, location, mic type, and user configured details. This information is used for file organisation and future reference.

The complex soundscape of a freshwater pond

This short audio-poster introduces the complex soundscape of a freshwater pond. It was created for the European Pond Conservation Network’s 9th Conference, and was subsequently displayed at the British Ecological Society ‘Ecology Across Borders 2021’ conference.

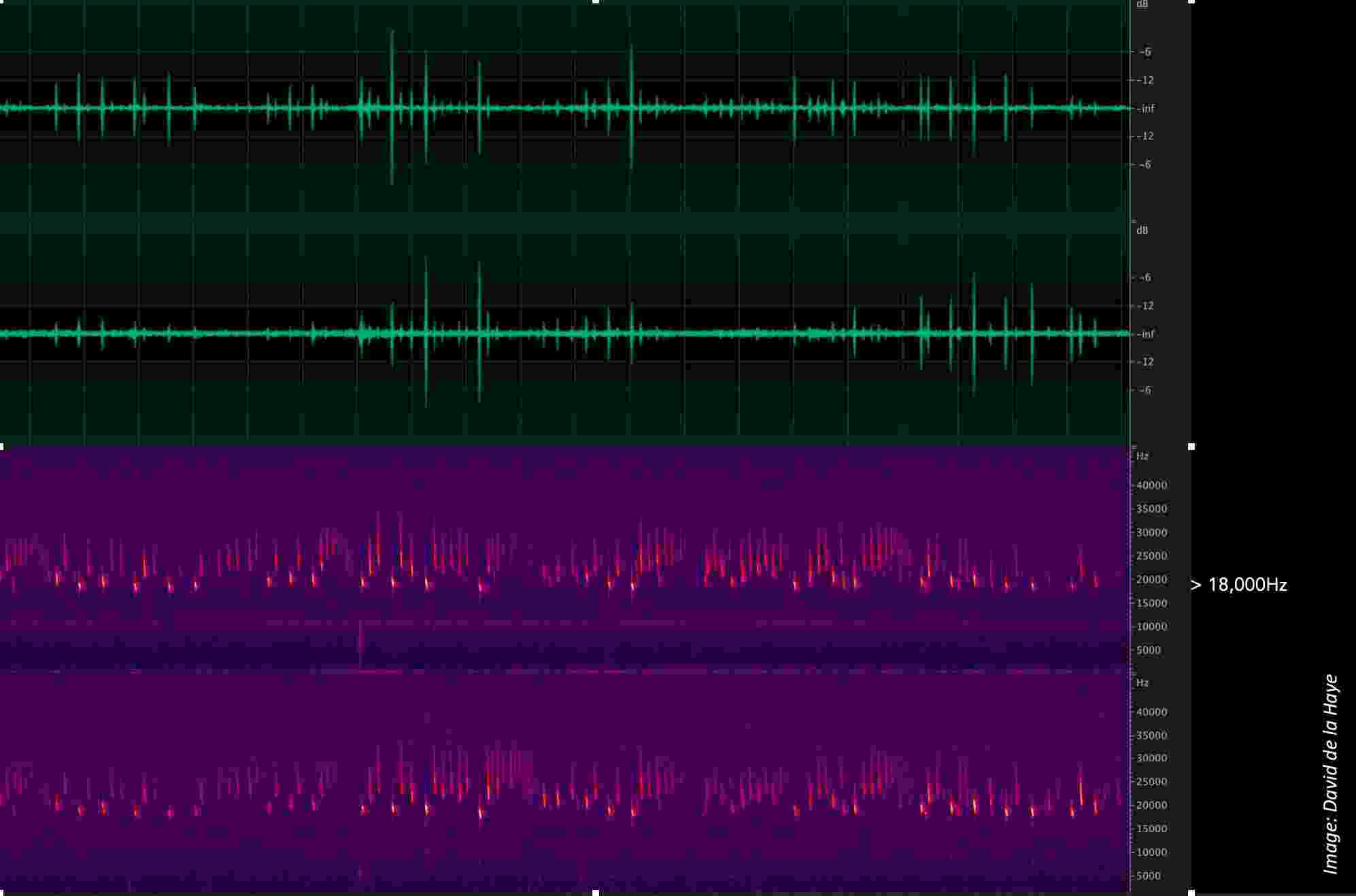

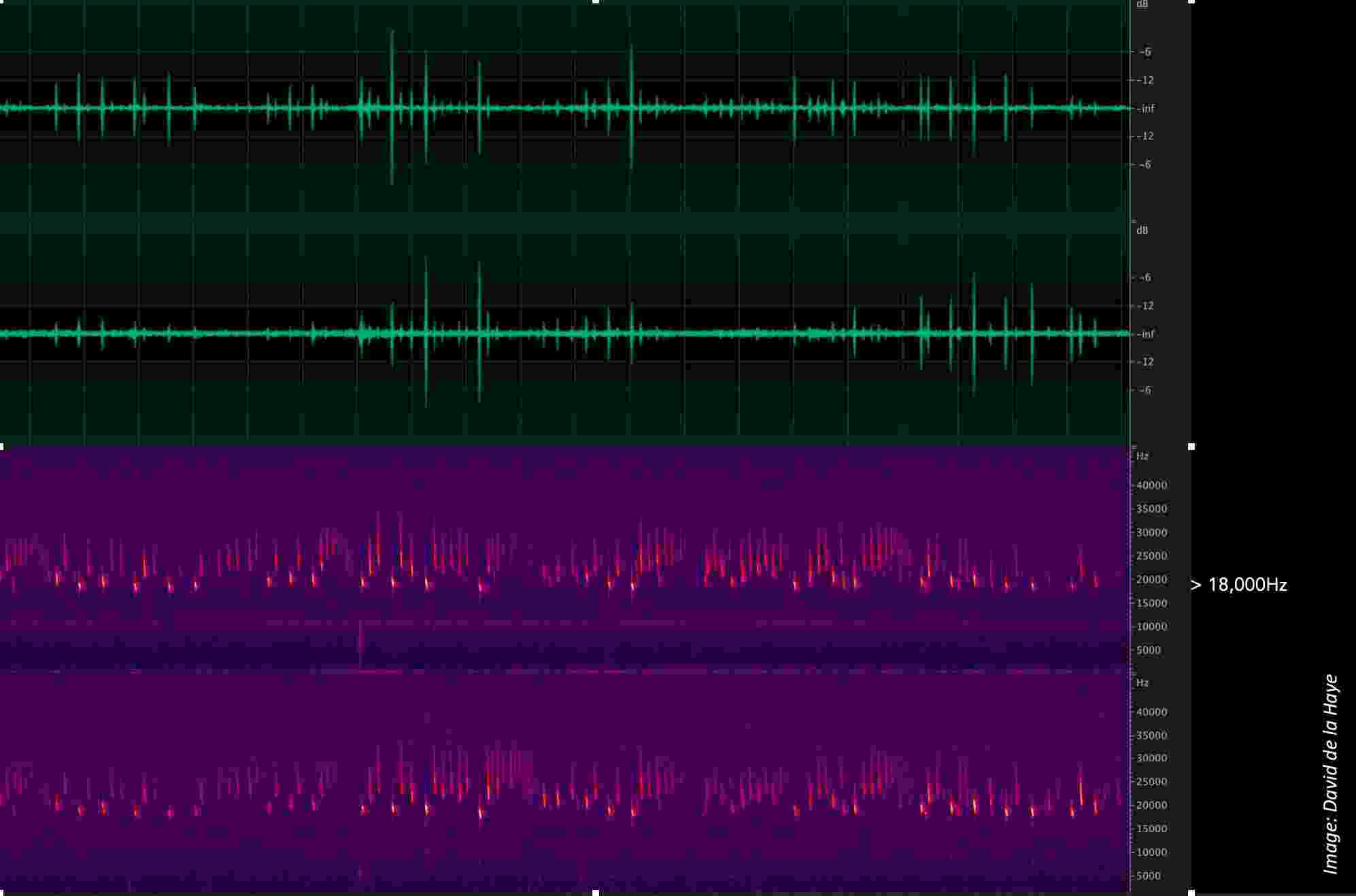

Image: David de la Haye

In the Studio

- The music studio can be used to subtly remove sonic artifacts or render completely new sounds through extensive manipulation.

- We can edit in the frequency domain to reveal sound below and above human thresholds. Lower sounds are infrasonic. Artists have explored tectonic movement, architectural resonance and elephant calls which fall into this category. Those above are called ultrasonic; bat and dolphin echolocation are a common examples, as are electromagnetic frequencies.

- Spectrogram images, as shown on the right, resemble graphic scores that composers such as Cornelius Cardew, John Cage and György Ligeti began to explore in the 1950s.

- Durational recordings can be time-compressed allowing us to experience a season within 15 minutes, or the slow shift of a glacier.

Image: Euan Preston

Ecological Advantages of Listening Methods

Freshwater

- We have entered the decade of ecosystem restoration, yet the sounds of our freshwater habitats remain largely undocumented.

- Freshwater environments in particular have gone largely unrecognised and remain widely excluded from many government policies, despite them providing refuge for two-thirds of the UK’s rarest species.

- Many freshwater arthropods are sensitive to environmental changes. Many also use sound to communicate. Acoustic surveys may provide a useful indictor of system health and provide new perspectives on freshwater protection.

- Surveying in this manner reduces disturbance to animals otherwise trapped in nets or containers; it is largely non-invasive.

Marine

- In marine environments, organisations such as the Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust have, over the last fifteen years, collected acoustic data on cetaceans and marine noise pollution. This has been cited as evidence of the need to designate Marine Protected Areas.

- Deployed hydrophone arrays, such as the Acoustic Network Gateway Buoy (ANGY, pictured) developed at Newcastle University, can remotely monitor offshore acoustic activity.

Community Engagement

- Raising awareness through participatory events, such as the series of sound-walks and coastal listening activities delivered through Durham Heritage Coast ‘SeaScapes Project’.

- Family listening-party events create a fun and accessible way for younger generations to experience first-hand the biodiversity of aquatic spaces.

- The acoustic data has huge potential for Environmental Agencies to monitor clean water (SDG6)

Summary

- Creativity can make water-based research more accessible and relatable.

- Bringing underwater soundscapes to the surface creates visibility of hidden ecosystems. It gives the a voice to the non-human.

- Sound provides a channel for deeply personal auditory experiences that resonate on the individual level and could foster environmental awareness for life under water.

If you would like to further discuss how sound methods might benefit your project, please contact David de la Haye

Email - david@daviddelahaye.co.uk

Website - www.daviddelahaye.co.uk