Dance as method

Dr Charlotte Veal

01 January 2023

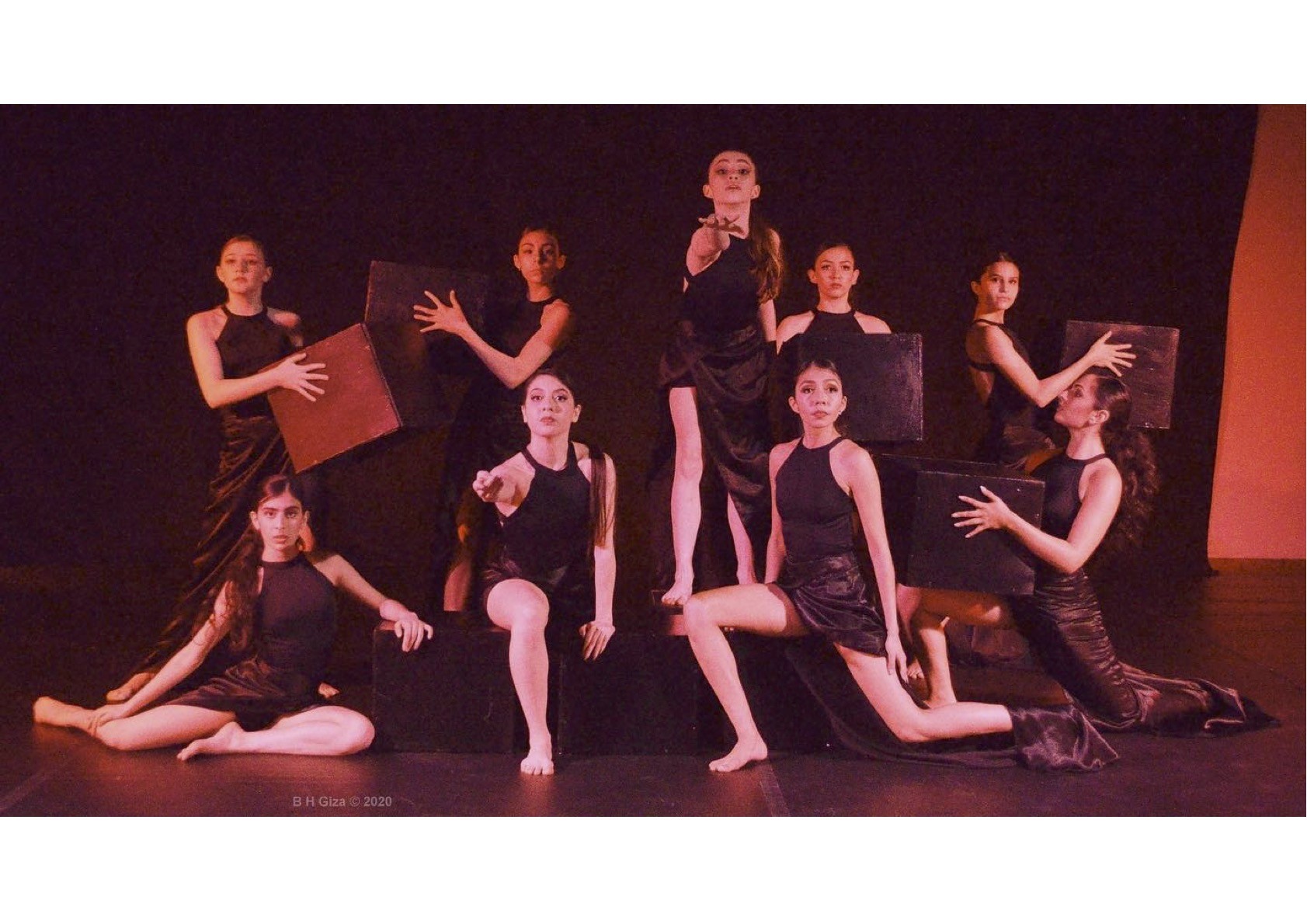

El Paso Ballet Theatre, Out of the Box 2020, Copyright: B.H.Giza 2020

Learning aims

To examine the critical and creative possibilities of dance in inter, multi- and trans-disciplinary research and its application in studying and responding to current and future global challenges and societal injustices.

Objectives

-

Examine what dance as method is and how it has been applied in a range of contexts

-

Explore dance ethnography as a means for generating new knowledge and investigating different perspectives

-

To trace forms of dance documentation and the recording of multi-sensual knowledge for communicating novel insight on issues of societal significance.

-

Critically examine how choreography and dance performance can facilitate encounters, provoke dialogue that supports attitude transformation, and/or expose everyday injustices, engaging diverse members of society.

-

Advance understanding of the value of dance-led methods and some of the key ethical considerations.

Outline of method

- Archaeological evidence shows that dancing took place as early as the 9th Millennium BC with depictions in the Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka India, and later, on Egyptian tombs. Throughout history, dance has been performed to serve various functions whether social, competitive, ceremonial, or martial.

- It has important:

- Cultural and religious value. Many scholars argue that prior to written language, dance (e.g. aesthetics, mime, symbolism) enabled for passing stories down through generations.

- It is widely recognised to have health value, with healing dances and trance believed to support meditation and to attain serenity.

- Dance holds important social value, strengthening ties of identity, inclusion, and community.

- Because dance has an important role to play in human communication and social interaction; because it supports our sense-making of the world; and because it enables for sharing experiences and expressing life – giving physical, emotional, spiritual and intellectual meaning – I argue it can be valuable as a research method. (see Cohen 1998, Kassing 2017).

I define dance methods as: the study, or co/production, of improvised or choreographed sequences of movement – whether professional or vernacular, traditional or modern, staged or un-staged – for doing scholarship into cultural, social, political, or environmental issues.

Scholars of performance have long recognised dance’s role in the doing of research, for engaging communities, and achieving impact. Since the late 1990s, its application has been realised more widely across the social, medical and physical sciences.

Three factors have contributed to this:

- Influence of new theories and ways of approaching the world, including Judith Butler’s work on the performative and Nigel Thrift’s Non-Representational Theory. Both foreground bodies, practice and multi-sensual knowledge.

- Mounting recognition across government for the arts and artists ability to contribute to society, whether in terms of social justice, conflict resolution, or health goals.

- A shift within the academy toward inter, multi- and trans-disciplinary scholarship.

Dance in Multidisciplinary Scholarship

Current examples in inter, multi or trans-disciplinary research include:

- Governance, landscape and security at the international border

- Disability and rights of marginal communities

- Gender based violence and cults of violence

- Post-conflict reconciliation

- Cultural diplomacy and statecraft

- Everyday politics of interculturalism

- Social justice and urban exclusions

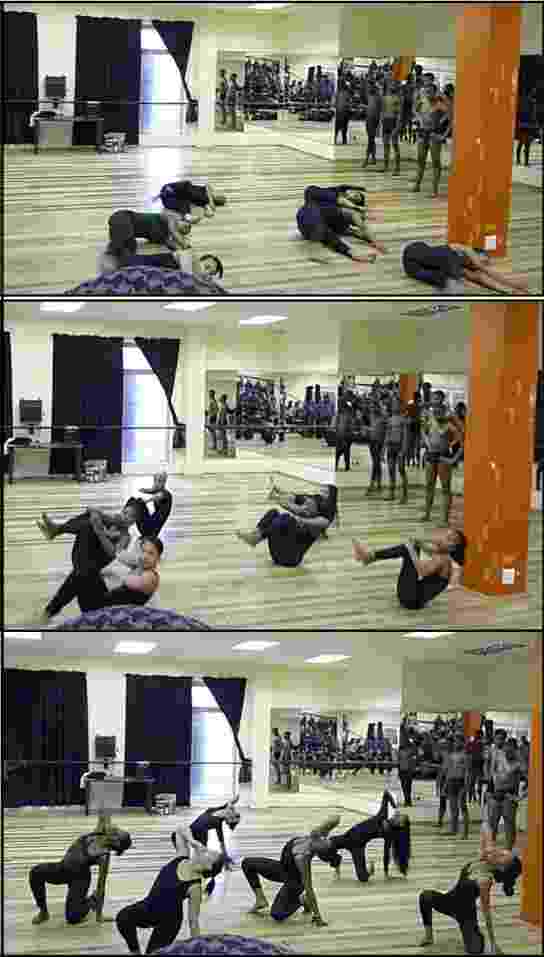

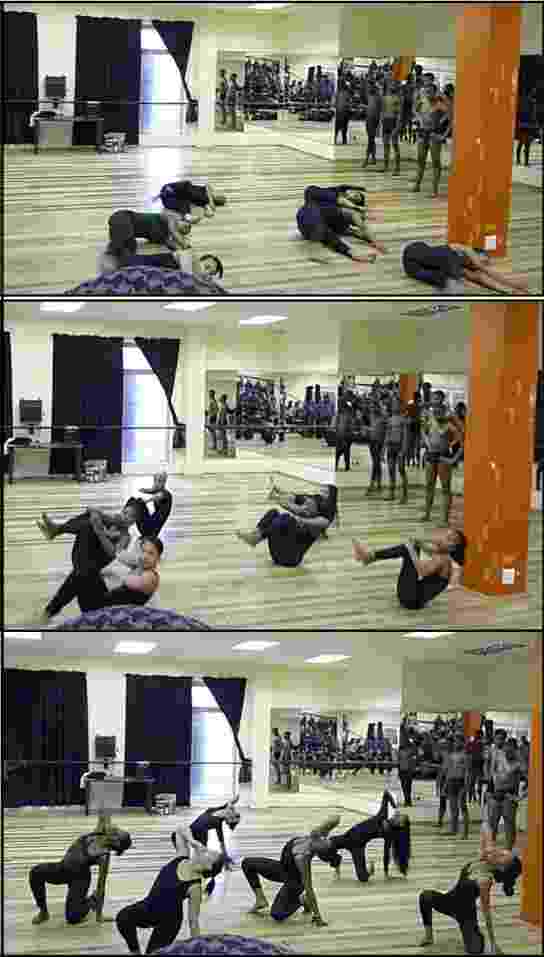

Rehearsals with BalletBoyz and Addisu Demissie, Stepback 2012, copyright Veal 2012

Introducing Dance as Method

My dance-led method incorporated three core components:

- Dance ethnography

- Dance documentation

- Dance performance and post-performance analysis

In practice: Dance Ethnography

In this video I offer four examples of how my dance ethnography materialised in the field.

In practice: Dance Documentation

Corporeal ‘data’ was recorded in my choreographer’s notebook (Veal 2016) and integrated Labanotation; performance cartography; performance cues and networks of embodied knowledge; and a movement material index.

Video footage from Stepback 2012, Copyright: Veal 2012

Dance performance and post-performance analysis

- Supporting in the staging of the performance

- Dance ethnography and dance documentation of the performance and informal conversations with audience

- Interviews or post-performance workshops

- Post-performance analysis (triangulation)

Dance For All Public Performance, copyright Veal 2013

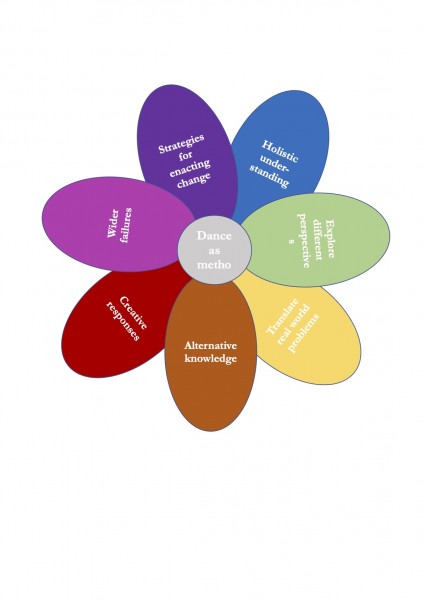

Dance ethnography and dance documentation in conjunction with performance and post-performance analysis, enables me to tease through how the dance process and dance product (the choreography) supports new:

- Holistic understanding on the chosen issue

- Perspectives grounded in the lived, everyday, cultural values of individuals/communities involves

- Ways of collaborating – new ways of doing research (inclusive, democratic, non-verbal)

- Medium for engaging audiences (aesthetically, affectively, emotionally)

- Devices for thinking/acting politically (new socio-political frames)

Differentiating this method from adjacent / similar methods

Dance-led methods share similarities with other arts-led methods including theatre.

Similarities

- Community-led supporting greater participation, democratising the research process

- Can be produced in ‘situ’ to the issue (grounded approach, situated)

- Learn about the perspectives of others (everyday, mundane, ordinary experiences)

- Creativity and experimentation throughout (trial, error, failure, reworked etc)

Differences

- Fully embodied / works through the scale of the body (visceral, bodily)

- Non-verbal communication and exchange (value in working beyond language barriers)

- Expressive/aesthetic and therefore open to interpretation

- Production of alternative forms of knowledge (multi-sensual, embodied, expressive)

Why use this method?

What areas of research is it appropriate for?

Dance can be used to study a plethora of research areas. It includes those that are concerned with deepening understanding about the social, cultural, political and environmental issues that impact ordinary people.

For Water Hub members this might include:

- Barriers and challenges to water security (e.g. among women)

- Cultural aspects/values of water (indigenous groups, local communities)

- Impacts of climate change, including drought (e.g. farmers)

- The experiences and struggles of those displaced by flooding (marginalisation, poverty).

Who could be involved – research participants, communities

Dance as method can be utilised with almost any group of participants, if that group are keen to be experimental, to explore an issue in a novel way, to engage with others differently, or to tell different stories through creative means.

- That community group does not need to be trained as dancers

- However, it works best with smaller groups (20-25) for practicality purposes/building rapport

Video footage, Slavery 2013. Copyright Veal 2013.

Key ethical considerations

There are key ethical considerations that must be addressed prior to embarking upon, and throughout the process of adopting, dance as method:

- Observing and watching (overt, covert)

- Participant consent (children, vulnerable groups)

- Power relations (researcher-researched, intra-community)

- Anonymity / confidentiality

- Safeguarding

Dance and performance also raise other ethical considerations:

- Aestheticizing violence, pain and suffering

- Retraumatising through reperforming past violences

- Aestheticising the issue, problem or challenge

- Political implications (politically sensitive subject)

- Cultural values (body, touch, clothing, gender relations)

Dancing Gender-based Violence, Slavery. Copyright Veal 2013.

Summary of Information

- Dance as research method emerged in the late 1990s. Still an under-developed methodological approach with no set framework

- Can be implemented in inter/multi/trans disciplinary research to support holistic understanding, different perspectives, translate real world problem and offer creative responses

- Participants do not need to be dancers (but worth thinking of skills necessary)

- Can provide a more inclusive space for research, work beyond more established hierarchies of knowledge/power, priorities other forms of knowledge

- My approach has comprised dance ethnography, dance documentation and performance and post-performance analysis

- Value in translating difficult subjects and engaging wider publics

- Application for Hub partners in thinking through barriers to water security, value of water or impacts on climate change.

Downloads

Bibliography & references

If you are keen to explore how dance-as-method could support your research, please contact Charlotte to discuss your idea: Charlotte.Veal@ncl.ac.uk